Anderson shelters

Anderson shelters were small, pre-fabricated air raid or bomb shelters, which civilians used for protection during air raid attacks.

The threat of war was looming throughout 1939, and the government made efforts to warn the population of the very real threats that would come from the skies. Hillingdon was not exempt from bombing.

As well as helpful pamphlets explaining what to do if war comes, the British government also provided Anderson shelters to any household that earned less than £5 a week. Men who earned more could purchase a shelter for £7.

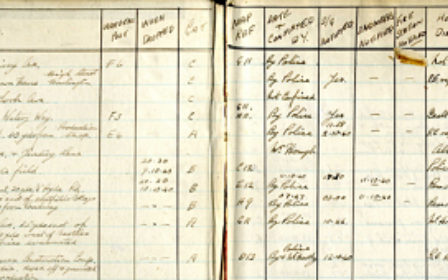

In our collection, there is a register for people in Hayes and Harlington who were on a waiting list for their own Anderson and Morrison shelters.

Morrison shelters were indoor cages that protected occupants if a bomb hit their house. They were a indoor alternative to the Anderson shelter and proved popular, as people often wanted to stay in their homes, even during air raids.

Elsie Howard, who was a child during the war recalls what is was like to wake up in the Anderson shelter:

"Every morning a cheery little thrush would wake us up and peer in at us!"

Whilst the Anderson shelter had lots of success, many people found them to be lacking in terms of quality. Lots of newspaper reports at the time show local residents of the Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette, searching for solutions to flooding and damp, which was apparently made worse by 'Middlesex clay', which is the foundation for most residential areas.

In the Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette, 27 December 1940, a local councilman argued that the psychological effects of residents living in these poor conditions were not being considered by those in charge of public safety.

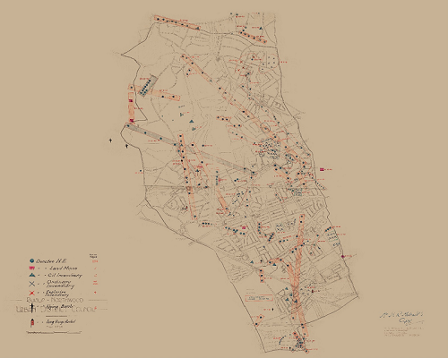

Alongside the Anderson shelter, there were a number of public air raid shelters that allowed people to take cover if they were out when the air raid siren sounded. In central London, the tube stations became a place of refuge, whereas those living on the outskirts would find their public shelters were in local schools, recreation grounds and even allotments. These shelters were organised by local Urban District Councils. The Hayes and Harlington Urban District Council created a map of Hayes and Harlington to let local residents know where their nearest public shelter was located.

By the end of the war, German bombing had killed 60,000 people in Britain, but the number would have been much higher without the Anderson shelters.